|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

The Lighthouse in the Woods (2014)

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

The challenge

One team at the Annenberg Innovation Lab's Autumn 2013 Think & Do on "Re-Envisioning the Home Entertainment Experience" was thrilled by what 360-degree viewing experiences could provide for horror productions such as FX's American Horror Story. Such tools could allow audiences to experience the element of surprise and suspense first-hand. This concept of "360-degree storytelling" resonates with multiple areas of the lab's Edison Project, beginning with virtual reality and moving into the connected home or connected city. The solution

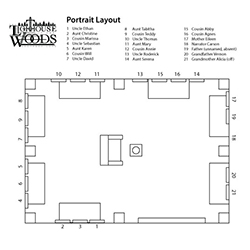

The Lighthouse in the Woods is an immersive ghost story. Donning an Oculus Rift, the user finds herself locked in a windowless study as a disembodied voice tells how, one by one, the narrator's family fell victim to a mysterious curse. Portraits on the walls illuminate as each family member is introduced, dim as each one falls, and re-illuminate as they come back. The audience member can move around the room, but cannot leave it, and has no control over how the story progresses – replicating the narrator's experience of impending doom and helplessness. The Lighthouse in the Woods leverages the Rift's unique sense of 360-degree immersion, but by removing nearly all of the audience's agency, it subverts the assumption that the Rift is a gaming device and delivers a storytelling experience more akin to film, TV or theater. This project also explores how storytelling could evolve for a connected home. The Lighthouse in the Woods uses portraits to tell its story because connected digital picture frames are one possible additional "screen" to use in a living room. For The Lighthouse in the Woods, I conceived of the project, wrote both the original short story and the script, created the models in a mix of 123D Design and Maya 2014, built and coded the prototype in Unity 4.3 for the Oculus Rift DK1, compiled the sound effects, and voiced the narrator. The Lighthouse in the Woods had its first public showing at the Innovation Lab's 2014 Evening of Innovation on April 23, 2014. The team

The tools

The Lighthouse in the Woods was created in Unity 4.3 for the Oculus Rift DK1, modeled in 123D Design 1.4 and Maya 2014, with additional assets generated in Adobe Photoshop CC and Apple GarageBand. The story

The lighthouse in the woods had always been there, to hear my grandfather tell it. It had always been there, and although it was square in the middle of our family's hundred-acre property, we had always been forbidden to go near it. It was our secret, nestled deep in the dense wood behind our family's ancestral home and surrounded by pine trees so impossibly tall that they enclosed the lighthouse completely. Its tip was not visible from the road, nor even from planes - my uncle Roderick once chartered a small Cessna just to check on it himself, and he returned jolly and satisfied that the lighthouse was truly safe from prying eyes in all directions. Or so we thought.

Of course the children of our family were the most inquisitive, asking endless questions about the origins of the lighthouse, the contents of the lighthouse, and especially why we couldn't tell anyone about it. "After all," my cousin Marissa pointed out in her most gratingly sniffy, uppity, singsongy tone on the day of the Fall, “it's a lighthouse in the middle of a for-est. That makes no sense at all. Why would anyone build a lighthouse where no one could see it, and with no wa-ter nearby?" My grandfather stared at her with his sharp hazel eyes, peering out from under his shock of dirty white hair. He was a twisted man in nearly every sense of the word - his frame had been wracked with some ancient degenerative disease that slowly knotted his spine and limbs into gnarled angles and curves, his arms so badly warped now that if he were to hold both arms out straight in front of him the veiny backs of each palsied hand would be facing one another - but his mind and his tongue, mercifully or cruelly depending on how you looked at it, remained straight and clear and razor-sharp. "My dear Marissa," Grandfather said in his strong, honey-smooth voice, "who are you to decide what makes sense and what does not? You don't know everything, and be grateful that you don't. You don't know the hearts and minds of the builders, you don't know if there was ever water here..." Marissa pounced. "But Grandfather," she said smugly, "I do know there was never water here. I did a project at school where we were told to research a subject at the City Hall. I chose to look up the history of this area's geography, and there was never any water here." Grandfather's eyes flashed. "That they know of." "No, Grandfather," Marissa insisted. "There was never any water here, ever. They did a study. They studied the minerals in the ground, they studied the makeup of the soil. There was never, ever, ever any water here!” Grandfather was silent for a moment. It was our turn to stare at him, while Marissa lifted her chin with a proud, defiant, nasty little smile and folded her arms across her chest, where her bosom was just starting to swell. There were eight of us in Grandfather's study that day, the sun-dappled and walnut-paneled room where he held court among his books and his notes and his cigars and his whiskey. Grandfather sat in his wingback armchair, a worn quilted blanket draped over his twisted legs, one hand tapping an irregular, uncontrollable staccato while the other cupped his chin in thought. Circled around him were the seven of us that called ourselves his grandchildren, six of us on footstools or cushions or mismatched chairs or the floor, with Marissa seated directly opposite Grandfather in a stiff-backed wooden chair, which was fitting. Marissa wore a prim red gingham dress, which her mother had almost certainly purchased from a Beverly Hills boutique specifically for this visit, complete with a matching red gingham bow nestled in a cascade of curls as black as the pristine patent leather shoes on her feet. The rest of us grandchildren were dressed nicely, to be sure - one didn't come to visit Grandfather in t-shirts and sneakers - but none of the rest of us placed as much stock in appearances and glamour as Marissa and her parents. Will, the second oldest behind Marissa, wore khakis and a polo shirt with a New York Yankees logo embroidered on his breast; chubby third-oldest Teddy sat on the floor beside Will in slacks and a pink Oxford shirt that strained at its seams; artsy fourth-oldest Annie sat beside Teddy fiddling with the constantly-evolving charm bracelet she wore on her right wrist and occasionally casting wandering glances out the windows; I sat beside Annie in my best jeans and a black dress shirt with my sleeves rolled up, trying to split my attention between watching the unfolding battle of wills between Marissa and Grandfather and ensuring that the twins, little Abby and Agnes, didn't put anything into their mouths as inappropriate as these impossible barbs coming out of Marissa's. When Grandfather finally spoke, it was in the lowest, coldest tone I ever heard, before or since. "My dear, you are very smart,” he said. “But you are also very stupid." Marissa started. "I beg your pardon?“ He cut her off. "Not all truths are to be found in records, nor in science, and especially not in the halls of politicians. Where is here, after all? Is here the soil beneath our feet? Is it the sky above our heads? Is it the rough amalgamation of atoms that make up these trees, these chairs, or these hands? And most of all, what is never? We know that this entire country was once covered in ice, and water before that." "But Grandfather," Marissa protested. "Surely you can't be saying that the lighthouse is older than -" "Be silent, girl," Grandfather snapped, his tone suddenly harsh. "I am saying that there are a great many things you do not know. One of them apparently being our First Law: that you do not talk of the Lighthouse to anyone outside this family, and you do not do anything that might call attention to it. Especially school projects in City Halls!" The turn in the atmosphere was abrupt and astonishing. My grandfather's voice had turned haggard and dangerous and feral, his tapping fingers now gripping the arm of his chair so fiercely that the leather creaked, his eyes now furious with rage. The change in Marissa was equally abrupt. The haughtiness was gone, the prideful sneer on her lips replaced by a horrified little 'o'. Her face was nearly the same perfect white as that now showing all the way around her blue irises. I had never seen Marissa terrified before now, but in three sentences Grandfather had shredded her pretentious mask and revealed the coward beneath. Worse, he wasn't finished. Draped over the arm of Grandfather's chair was a wire with a push-button, which he now squeezed between his thumb and forefinger. Instantly the door to the parlor swung open and Christopher, Grandfather's personal assistant and chief valet, appeared. "Yes, sir?" Grandfather pointed at Marissa. "Take this one to her parents and tell them to leave at once. Her actions have endangered our family and they have failed to teach her respect for our laws, our traditions, or for me. Until they have done so, none of them are welcome on family land." In a blink, Christopher was beside Marissa, seizing her shoulder and lifting her forcefully out of her chair. He paid no heed to her screeching, sobbing and wailing as he steered her out of the study, then the door slammed shut behind them and the room fell abruptly, uncomfortably silent. The rest of us stared at Grandfather. Looking back, I don't think I had ever known true fear before that day, not really. Sure, there had been plenty of times when my mother had punished me for doing dumb things, like breaking one of her good china plates when running through the house or for trying out a few choice swear words when she was within earshot, but nothing compared to Grandfather's exile of Marissa - and by extension Aunt Clarissa and Uncle Ethan - in only a few seconds. Which, ironically, was about as long as the awkward silence in the parlor lasted until both Abby and Agnes began to cry. I picked up Agnes and began to comfort her while Annie did the same for Abby, but they were having none of it. Luckily, their wailing extinguished Grandfather's fury, and he sagged in his chair like a man deflated, his palsied tapping now reduced to a ragged twitch and his other hand covering his eyes as he dropped his chin to his chest. Teddy moved to speak, but Will, always so wise for his age, placed a hand on Teddy's shoulder and shook his head. We sat there for a long minute like that, two of us crying loudly and the rest of us likely wishing we could do the same, and then the parlor door burst open again. Through it flowed a flood of people - first Christopher, his face flushed and his mouth working silently, and then a rush of aunts and uncles chattering in a maddening din. I was about to heave a sigh of relief and hand Agnes over to her mother when Christopher's mouth finally remembered how to work. "The girl broke free and fled," Grandfather's man cried above the ruckus. "Her parents and some others are searching for her now, but I'm afraid..." Grandfather rose from his chair, a mixture of horror and fury on his face. "Stop her," he whispered. "She's heading for the lighthouse!"

All was chaos. Aunt Serena, Agnes and Abby's mother, took the twins and bundled them off to a bedroom somewhere. Uncle Sebastian and Aunt Karen, Will's parents, seized him by the wrist and rushed outside, presumably to find Marissa. Teddy and his parents followed suit, accompanied by Christopher, but Annie and her mother Mary stayed with Grandfather. Annie's father and Marissa's parents had all already gone out in search of her as soon as she'd fled. This left my mother and I alone on the mansion's porch, listening to the distant cries of Marissa's name coming from off in the woods and the incessant wailing of the twins from deep in the mansion. I looked up at my mother. She was a tall, pale woman, slender with whitish blonde hair and green eyes that shone from a face that normally radiated bravery, strength and confidence, characteristics which had served her well as a single mother. Not now. Instead I saw an alien, anxious helplessness that I'd seen before on the face of Aunt Tabitha, Teddy's mother, but never on hers. I reached out and took her hand, and she looked down at me as if realizing I was there for the first time. She forced a smile onto her lips - although she couldn't quite bear to bring the lie up to her eyes - and guided me into the kitchen. I was on my third cookie when the thunderclap shook the house. The glass rattled in the cupboards, the pendant lights over the stove swung furiously back and forth, and the screams from both inside and outside the house doubled in volume, and then, somehow, were halved. A moment later, Aunt Serena burst from the bedroom wailing and clutching a horrifically still Agnes to her breast. The study doors flew open and Annie stumbled out with tears running down her face, her mother staggering after her with a ghostly look in her eyes. The thunderclap had heralded several things happening at once. First, the slamming of the lighthouse's massive and awful door behind Marissa. Her parents had almost caught her, but the back of that red gingham dress and a flash from the gold buckles on her shoes were the last her parents ever saw of her. Second, the sudden and inexplicable deaths of my grandfather, Cousin Agnes, Uncle Sebastian, Aunt Tabitha, Cousin Annie's father Uncle Thomas, the twins' father Uncle Roderick, both of Marissa's parents and, presumably, my own father. They simply stopped, crumpling to the ground wherever they stood like so many puppets with their strings cut. One of every pair, as we'd say later, and doubly so where the blood of the trespasser was strongest. Third, the onset of the great and terrible curse that would plague what remained of my family for the next twenty-five years. As Annie would swear later, my grandfather had died rocking back and forth in his chair, clutching a small photograph of my late grandmother and muttering the same phrase over and over beneath his breath: "The Lighthouse has laws, and, God save us, we have broken them." Obviously, He didn't. The next twenty-five years saw the Lux family collapse into ruin. The massive funeral that we held at the mansion for our lost loved ones might as well have been a funeral for all of our own fortunes, for any luck or grace that we might have been destined to enjoy had been just as quickly snuffed out when Marissa stepped through that door. In some ways, the event brought those of us who remained closer together as we collapsed ranks against the outside world. There were questions, of course - God, were there questions! Dozens of ratfaced reporters smelled a story, some mass suicide or some new type of toxic event that might be used to threaten and thrill countless cow-eyed daytime TV addicts. We turned them away, each and every one. Christopher had, freely and of his own invention, fed them a story about the wild mushrooms he'd gathered for the evening's risotto tragically turning out to be poisonous. Of course none of us pressed charges. In other ways, the event strained the bonds between us to snapping. All of us stayed clustered in the mansion as long as we could, huddling together for strength and comfort despite all of us feeling an evil eye peering down at us from that damned tower. The remaining adults would take turns going out to sit beside it for hours at a time, watching for any glint and listening for any rustle that might indicate that Marissa was still alive inside. They would occasionally call her name, to be met only with echoes. That insidious tower had, for all practical intents and purposes, devoured my cousin, swallowing her up and disappearing her from the surface of the earth. None of us questioned the strangeness of the disappearance; if whatever darkness lived inside the lighthouse could strike eight people dead in a moment, how difficult could it have been for that same power to wink a fourteen-year-old girl out of existence? So yes, we stayed, but as the hours turned into days and then into weeks, there were practical matters in the outside world that could no longer be ignored. One by one we dispersed, fretfully citing jobs or mortgages or other relatives that had to be tended. My mother and I were the next to last to leave, and in fact were the very last to go; as Annie's mother Mary had been the oldest of the six children of Vernon Lux, the family mansion - and its horrible stewardship - had passed to her. My mother and I stayed as long as we could, and in fact our departure was a tearful one filled with promises of swift returns and frequent phone calls, but eventually we too had to return to our lives in Chicago. Perhaps we thought that the curse was somehow constrained to the soil around the mansion, that we could somehow outdrive, outfly or otherwise outrun it. As we soon sadly discovered, this was not the case. One by one the remnants of the Lux family fell into ruin. Will's mother contracted breast cancer and was dead within the year. Grief-stricken, Will disappeared the night of his mother's funeral and was never seen again. Teddy's father lost his job as a high-powered trading executive in New York and crawled into the bottle, leaving Teddy to drop out of school and take up odd jobs to make ends meet. One of those odd jobs involved delivering pizzas to some very dangerous neighborhoods, and one night he was mugged and killed for the thirty-seven dollars in pizza money he carried. Teddy's father killed himself the next day. As much as Aunt Serena tried to keep Abby safe, there is only so much a person can do. The two of them were aboard an ill-fated plane that flew afoul of a storm somewhere over rural Indiana and crashed into a lake an hour or so west of Indianapolis. There were no survivors. My own mother was struck and killed by a drunk driver the week before my twenty-first birthday. I was called out of an art history class in my junior year at Oberlin to receive the news. In a way, it was a relief - when you know your family is cursed, you're constantly waiting for phone calls. Aunt Mary, bizarrely, died in her sleep. The doctor said that it was an aneurysm, the kind of thing that had been brewing in her brain tissue even before Marissa's damnation of the family, which left me to wonder if perhaps the mansion did have some kind of protective powers. Finally, on the night of September 24th, precisely twenty-five years to the day after Marissa disappeared into the lighthouse, I was awakened from a deep sleep by my cell phone ringing. I sat up in bed, waking easily from the rough half-sleep that I'd developed as a kind of self-preservation tactic (it's much harder for a random thing to kill you when you sleep with one eye open), and reached for the phone. As I did so, I wondered how the curse had finally gotten Cousin Annie, how it had gotten past whatever mystical defenses the Lux mansion granted, and that now I was the only one left - but then I saw the caller ID. It was Annie. "Hello?" "Carter?" Annie's voice was shaken, tremulous. "Yeah, Annie, it's me. What's happened? Is everything all right?" "It..." Annie cleared her throat, clearly struggling to regain her composure. "Carter, listen. I know this is impossible, but... You have to come." I pinched the bridge of my nose, where I could feel the migraine already beginning to form. "Annie, I can't - we're opening a new exhibition at the gallery in three days and I can't just..." "It's Marissa," Annie wailed. "Oh, God, Carter, it's Marissa - she's come back!"

What could I do? I was on the next plane out. According to Annie, she'd been roused from her own bed a little after 3 AM that morning by a thunderous pounding at the door. She'd fetched her gun – cursed or not, any wise woman living alone in the middle of a forest is bound to take precautions – and gone to answer it, and was damned lucky the gun hadn't gone off when it had clattered to the floor as soon as Annie peered through the peephole. For a moment, Annie thought that Marissa was a ghost. Impossibly, although admittedly perhaps among the least on the list of my family's impossible things, Marissa hadn't aged a day. She was still the same size, still wore the same prim red gingham dress and the same black patent leather shoes with gold buckles, and neither the dress nor the shoes had a single scratch or tear or scuff. However, Marissa's hair no longer matched her shoes. Instead, it was now a pure alabaster white, as was her skin, and so were her eyes. Every cell of her seemed to have had all its color stripped away, so utterly bleached to a ghostly white that she looked more like a porcelain doll than even the palest of albinos. You hear stories of people going white with fear, of having their hair turn white after a shock, and Annie and I both agreed that had to been what happened here, because whatever Marissa had seen inside that lighthouse had also melted her mind. As much as I wanted to hate her for what she had done, what she had cost us, the Marissa that returned to us was not the haughty little brat that had damned our family. She was barely Marissa at all, or even an echo of herself. She was more an echo of Grandfather – in the same way that he died repeating that haunting refrain – the Lighthouse has laws, and, God help us, we have broken them – Marissa came back to life whispering another chorus, over and over and over again, and nothing else. They came back, they come back, and they're coming back, if Carter goes in to save us. They came back, they come back, and they're coming back, if Carter goes in to save us. Of course, Annie didn't tell me that part until I got to the mansion. If she had, I might not have flown back at all. No, instead, she waited to let me hear that song from Marissa's lips herself. Annie had greeted me at the door and taken me straight to the bedroom where she'd stashed Marissa, and that's where we found her, standing on the bed and staring at the wall, and even though Annie had been careful to give Marissa a room on the side of the mansion that faced away from the lighthouse, I knew that I could trace Marissa's gaze straight through the wall and the house and the trees to that damn tower, as surely as following a compass' needle. When I heard Marissa whispering, I leaned in to hear what she way saying. When I did, I recoiled in abject terror. I spun to face Annie, my eyes wide and the bottom falling out of my stomach. “What does she mean, Annie?” I demanded. “Why me? You're the oldest, you're the heir to the mansion, you're the keeper of the lighthouse! Why in God's name does it want me?” Annie opened her mouth to speak, and then let out a bloodcurdling scream. It was the last noise she ever made. At first I thought it was another thunderclap, the noise was so loud. Then I saw Annie go reeling backwards, a red rose blooming on her breast. I whirled around to face Marissa, suddenly sure that the curse had found me at last. It had, of course. Just in a much more prolonged, roundabout way. Marissa had found Annie's gun. The first shot narrowed the remaining members of the house of Lux to two. I stared at Marissa, frozen and dumbstruck and sure I was next, and, damn me, I wasn't fast enough to stop what she did next. Marissa pulled the gun up and fired the second shot into her own mouth.

Again, what else could I do? I thought of fleeing the house, right then and there. Just getting in my car and driving as fast and as far as my credit cards would take me, anywhere that might somehow, some way grant me refuge from this damnable curse. But then I knew, just like how it found Serena and Abby in the Indiana sky, there was nowhere I could possibly go. They came back, they come back, and they're coming back, if Carter goes in to save us. What the hell could that even mean? Who would come back? My family? The lighthouse let Marissa go, and somehow, ghostly whiteness aside, the lighthouse had restored or preserved her youth. Was it possible? If the lighthouse could curse us all and strike us down one by one, was it possible that it could restore us as well? What else could I do? What choice did I have?

So here I am, forty-eight hours after Annie's call, twenty-five years and two days after the start of the fall of the house of Lux, in the most impossible of impossible places, the last place I thought I'd ever, ever, find myself: standing in front of that damned tower, staring up at it, trying not to look at the door. There is a wind howling through the trees, rustling the branches, making some of them tap against the outer wall of the lighthouse in a rough staccato that sounds for all the world like my grandfather's palsied fingers, tapping away somewhere overhead. For all I know, that might actually be him up there, or his revenant, or something else. For all I know, all of them are in there, waiting. Waiting for me to come and… What? Save them? Join them? Either way, what else can I do? I reach out, and my fingertips brush the doorknob. It's cold. I still don't look at it. I close my eyes, take a deep breath, seize the doorknob, and give it a turn. There is a blinding flash, as if the lighthouse has suddenly been reignited. I do not open my eyes. I step through the

|

||||||||||||||||||